HC-7 RESCUE 116(1) 7-Aug-1972 (Monday)

HH-3A Sikorsky Seaking helo Det 110 Big Mother #60

USS England (DLG-22) Combat Night (2) INLAND – 9.3 miles

Water: 85⁰ Air: 84⁰ Wind: Light Sea State: N/A

Pilot – LT Harry J. Zinser

Co-pilot – LT William D. Young

1st crew – AE-3 Douglas G. Ankeny

2nd crew –AMHAN Matthew (n) Szymanski

06/Aug/1972

Alert received – 2210: ship called emergency flight quarters – crew asleep preparing for a midnight alert five

Vehicle departed – 2220: 113 miles –

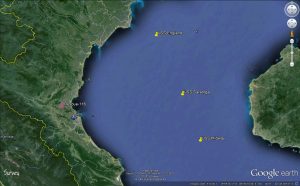

Arrived on scene – 2320 : arrived on station 2 miles East of Hon Matt island 07/Aug/1972

Located survivor – 0222: vectors from survivor and OSC/strobe – darkness/enemy fire/false pencil flares/strobes

Begin retrieval – 0223: landed in rice patty

Ended retrieval – 0223: survivor entered through cargo door

Survivor disembarked – 0300: ambulatory – USS Cleveland (LPD – 7)

Total SAR time – this vehicle – Four hours and 40 minutes.

A-7A Corsair (Canyon Passage 407) (11) 153147 VA-105, (Gunslinger) USN,

USS Saratoga (CVA-60)

Lt James R. Lloyd

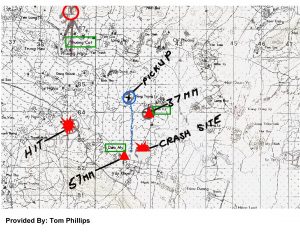

Another Corsair was lost over North Vietnam on the 6th after nightfall. A section of aircraft was flying an armed reconnaissance mission near Vinh when the aircraft picked up a signal indicating that they were being tracked by a Fran Song SAM radar and that a missile had been launched. The aircraft started jinking but at 3,500 feet and 300 knots Lt Lloyd’s Corsair was hit and the port wing started to disintegrate. The aircraft caught fire, the hydraulics failed and the controls stiffened. Lt Lloyd ejected as the aircraft pitched nose down. He landed safely near My Ngoc. 20 miles northwest of Vinh and was later rescued by a Navy HH-3A SAR helicopter. It could not be determined whether the aircraft had been hit by a SAM or by 37mm AAA, which was also seen at the same time as the SAM launch.

Statement by Lt. James R. Lloyd (retyped from an original)

At approximately 21:00, 06 August LCDR Bell and myself were vectored from our mission of RESCAP at HON NIEU to search out and destroy trucks that were spotted in the vicinity of Hwy. 72 north of VINH approximately several miles after dropping my ordnance on the target I proceeded north to follow CANYON 1. Immediately I got a SAM indication through my shrike system and spotted a SAM lifting at 1200′. Being slow and at 7000 feet I attempted to fire my shrike. (I’ll never know if I gave it enough time to actually fire before pulling right). I dove for the deck and began picking up 37 mm around my canopy. I felt a heavy thud on my left wing, saw a flash and began a heavy port roll and I saw my wing come apart. The hydraulics were lost and I went to a nose down altitude and ejected passing through 2000′ MSL. Ejection was normal and I had 2-3 swings before landing 100 feet from the fireball. After getting out of my chute, and seat pan, and mask, I ran for the low hills 3/4 miles before realizing I was across from a village. I hid and could see and hear voice, dogs barking. In the one and a half hours I stayed there I saw approximately 100 people, yelling, banging dishes and drums, people of all ages and sexes. 11 people passed by 10′ without seeing me. I was in the open but I was dressed dark and blended in well. After assuring voice communications with Bernie Smith and Art Bell, I realized I was in the middle of heavy small arms, at least one 37mm site and one 57mm site, 3000 meters away. There were people all over and most of them had guns. I felt relativity safe. Where I was even though I could hear half a dozen men about 30 feet away on the other side of my bush. I told the A/C to hold Big Mother and that it wasn’t safe here and that I’d try to move north. I tracked north because every time and aircraft would fly over, the whole world around me would open up all except north of me beyond 1-2 miles. I notified them I’d be off the air for awhile. I took both radios, my remaining water bottle and a flare which I stuck in my suit. I took both radios, and left my vest due to the fact it was heavy and noisy. I elected to leave my 38 pistol behind as well as my large compass because the clatter was very noisy. I spent 10 minutes crawling out of the bush and crawled 100 yards away from the people chatting away only to realize I lost everything, even my 2 radios. I crawled back, found my PRC-90 radio lying on my vest and crawled away again. I only got 25 yards when I heard and saw 2 men coming up behind me. I lay down and heard them walk by only to stop, turn around and came back. When I felt a gun in my back, I knew I was a goner. There was some more chattering and then the sounds of footsteps running up the hill. I slowly rolled over to see what I was faced with only to see both of them gone in which case I got up and ran like hell on a heading 30 degrees from theirs. Bernie or Art would fly over low they’d turn their lights on for a mark and take heavy, fairly accurate ground fire-up to 57mm. I’d tell them that only to hear “Rog” or “Gotcha”. Their voices in the area was very encouraging. Meanwhile, I was running, everybody opened up with fully automatic weapon. I could hear bullets a buzzing by and thought they spotted me but later found out it was random shooting and I strongly felt that their “dead” pilot had fled to the cairn peaks where everyone headed. After a half-mile or so, I began crawling, it made less noise, and I could see the horizon better. I again heard voices ahead of me and saw figures coming head on to the path. Had I been walking I wouldn’t have seen them in time. I crawled approximately 5 feet off the trail (dry partitions between rice paddies) I laid down. They walked by chattering their hideous gibberish and never saw me. I’d say there were 8-12 in total men and women. I got up and proceeded my crawling. Throughout the next 2 and one half hours, I contacted Bernie or Art numerous times to assure them my condition. I began realizing my only radio was getting weak and I had left my spare batteries behind. Any chance I had, I might add, was for a pickup before dawn. At night, especially crawling, I was almost totally undetected. But with daylight I could be spotted a mile away in that 6” rice and 10″ smelly water; plus I was leaving a faint trail of broken rice stalks. I mentioned this to Bernie who continued to reassure me the helo was awaiting my call. I continued until the scattered voice and gunshots became quite common at least in my vicinity. I called CANYON 1 to bring BIG MOTHER in, which he acknowledged. He told me it’d be at least a 30 minute wait in which time I relaxed in a small bush. It wasn’t until then did I realize how sore I was. My ankles really were hurting now, my hands and knees were sore and I had an immense thirst. I also reeked of human waste and stagnant water. My face itched from the mud I applied, but besides giving cover, it kept the mosquitoes off. I started hearing aircraft and pickup ACE 504, CDR ERNEST , who I recognized right away. I made it a point to know who was flying each aircraft in the area to fight the loneliness. At first, he didn’t hear me and I felt my radio had gone bad for good. He flew over with his lights on and once overhead he picked up my transmissions. He then vectored BIG MOTHER INTO within a mile of where I was. I began bringing the helo in from there while 504 and the other escorts remained above. I had no means of illumination except my strobe light which I didn’t use until they were within 100 yards. As I vectored them, they took considerable small arms. By now the NVN were attracted into the area and I was afraid to step out into the open, the helo had all their lights on including a flood lamp. I was afraid it was just a matter of time that they’d go down. The two waist gunners were really hosing the oncoming enemy. They asked several time for a signal which I acknowledged with my strobe, only after I called “strobe don’t fire”. After circling for better an 5 minute looking for my exact position and taking heavy ground fire they spotted me and maneuvered within 100 feet or so with their penetrator down. I could see occasional movement of moving figures in the perimeter I considerable gunfire. I expected any second to be shot. I ran up the penetrator, snapped my snap link into it, sat down with my head down, I waited Nothing. Looked up to see the helo was on the ground and sitting on a coil of wire. I jumped in and the crewman put up his gun then continued to fire. I could see the tracers outside the helo couldn’t tell where they were going or from where they came. It was an outstanding performance of bravery, skill, and determination played by every pilot and crewman involved.

“HC-7 guys – Thanks for your heroic efforts throughout the war. There are a lot of us who are alive because you were all willing to risk it all for us”

Jim Lloyd 2006 HC-7 reunion;

“FOUNDATION” Vol-25, Number 2, Fall 2004 – by: Capt Harry J. Zinser, USN (Ret.)

“BIG MOTHER to the RESCUE”

The morning of 6 August 1972 began like any other for a Big Mother pilot in the Tonkin Gulf. Flying armor-plated Sikorsky HH-3A Sea Kings from carri¬ers and non-aviation ships with helo decks, our crews stood the SAR watch in the gulf 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Alert 5s, 15s and 30s merged into always being ready to launch at the beckoning 1MC call of “Launch the alert helo.” Rare, indeed, was the occasion when a Big Mother crew could not get airborne within minutes of an alert launch call. A permanent fixture on Yankee Station, the combat-equipped HH-3As of HC-7 Det. 110 and their crews exercised their squad¬ron’s motto: “Combat SAR prevents POWs.”

With no single carrier to call home, we constantly cross-decked from the “headed for lib¬erty” carrier to the “coming back on duty” car¬rier. Helos were swapped out as needed from Det Cubi Point, where squadron personnel per¬formed 0-level maintenance. Crews swapped out from NAS Atsugi between 1967 and 1971. After HC-7 made a homeport change in 1971 from Atsugi to NAS Imperial Beach, California, crews rotated in from Imperial Beach until the end of the Vietnam War.

Little did our crew realize, flying in Big Mother 60 that August morning, that before day’s end we would log 11.2 hours of flight time, including a night landing under intense enemy fire in North Vietnam. The briefing and launch from USS Midway (CVA-41), holding position on Yankee Station, was uneventful. Midway was scheduled to be relieved by USS Saratoga (CVA-60) within two or three days, so we car¬ried along our entire seabag. Our mission was straightforward and routine: Launch to relieve a fellow Big Mother crew at North SAR and drop off pony (mail and movies) to ships while en route.

With North SAR more than 200 miles away and several scheduled pony drops in between, our crew began discussing options for refueling and how to utilize our flight plan in order to test-fire the GAU-2B mini-gun and conduct practice SAR work. I alternated flying right and left seat with Lieutenant Bill Young, a former H-2 Sea-sprite pilot and recently transitioned H-3 driver. Our first crewman, Aviation Electrician’s Mate Third Class Douglas “Stretch” Ankney, and SAR swimmer, Aviation Structural Mechanic Airman Matthew Szymanski, were always willing and eager to train, especially when it came to firing the mini-gun. Szymanski, a former Huey gunner from HAL-3, was quite adept at firing the M-60 and mini-gun. His experience would soon prove valuable.

After taking on fuel at the last small boy before arriving at North SAR (call sign Oswald) we kicked out a smoke as a reference point and practiced a SAR scenario which included firing weapons, simulating swimmer drops and per¬forming quick stops and jinking maneuvers. Quick stops and jinking maneuvers were best accomplished with light fuel loads as a result of the high temperatures and high density altitude environment of the Tonkin Gulf. We logged more than five hours of flight time, including several pony drops, small deck landings and refueling and a full cycle of combat SAR maneuvers before putting down aboard USS England (DLG-22).

After nominal time on deck and a chance to grab some quick chow, we launched in the late afternoon to pre-position near the North Vietnam coast for a Navy-Air Force joint operation. Maintaining a prepositioned orbit near a sortie’s coast-in point was a major factor in many suc-cessful rescues throughout the squadron’s his¬tory. On numerous occasions, Big Mother crews would be on top of pilots only seconds after the pilots hit the water, thanks to our prepositioning at the coast-in and coast-out points. Big Mother crews on non-aviation ships covered night sor¬ties by remaining on deck with all systems hot and monitoring the strike frequencies in order to launch at a moment’s notice. This was called the Alert-5.

Although night takeoff from non-aviation ships was permitted, nighttime recoveries were not authorized, thanks to limited deck lighting. This limitation dictated that crews launching at night had to recover elsewhere, usually the clos¬est amphibious transport dock or aircraft carrier, resulting in the loss of a Big Mother asset in that area until replaced. Therefore, most night sorties were covered by Big Mother crews standing the Alert-5 on deck until all chicks reported feet wet, indicating that all aircraft had reached the shore¬line of the gulf safely and were en route to their homebase.

With our preposition completed, we landed a second time aboard USS England and quickly completed our tasks: conducting a turn-around inspection, finding a berthing location and eating chow. We then secured for the evening, realiz¬ing that we were now the designated North SAR Alert Helo until relieved. Having logged more than 6.5 hours of flight time already, we were ready to settle down for the evening and wait for the next morning’s message traffic to find out when we could expect our relief crew.

At approximately 2200, I decided to make a quick pass through the Combat Information Center (CIC). The rest of the crew had already retired to their sleeping quarters. As I entered CIC, one of the chiefs called me over to his scope and said, “Hey, lieutenant, they’re preparing to

launch one of your Big Mothers for an overland rescue’

Although our crews routinely performed res¬cues, both opposed and unopposed, over water and near the shore, the last time a Big Mother or Clementine (HC-7 det. 104-107) crew had pen-etrated North Vietnam was in 1968. That daring rescue was performed by Lieutenant Clyde E. Lassen, who received the Medal of Honor and would later have a ship, the USS Lassen (DDG-82), named in his honor. [ Added HC-7 history – The last time HC-7 crews penetrated North Vietnam – rescue 53, 30-Aug-1968 and rescue 54, 6-Sep-1968 — ]

The Big Mother that was called on to launch was our sister crew, standing the Alert-5 on South SAR. At the time, there had been no voice communication with the downed pilot and the launch of a Big Mother would most likely be a routine measure. Obtaining positive voice con¬tact with a downed airman was one of the hard lessons learned for overland rescue attempts. Furthermore, the downed pilot’s position was more than 20 miles inland in a heavily fortified

area of North Vietnam.

Nevertheless, the Big Mother aboard South SAR was called to launch. More than 200 miles south of our position, South SAR was the closest asset to the scene of action. As we intently moni¬tored the strike frequency, we heard many calls from Midway to South SAR inquiring if their Big Mother was airborne. After several negative replies, South SAR called that her Big Mother had electrical difficulties and would not be launch¬ing. We later learned that all flight instruments had been zapped while external power was being applied. The dreadful moment of silence was pierced by the next radio call from CTF-77 aboard USS Midway “Oswald, this is Jehovah. Launch your Big Mother”

All eyes in CIC focused on me standing next to the chief. We suddenly realized that Jehovah, the call sign used only by Task Force 77, was summoning the SAR asset on North SAR, more than 200 miles to the north, to launch. I thought, “Certainly there has to be a Big Mother asset

aboard Midway that could respond quicker than we!” The Yankee Station carrier was easily 100 miles closer to the scene than we. Our fuel load of 3,000 pounds put our warbird at, if not over, max gross weight. Because we would be return¬ing to a different carrier than when we launched, in addition to our personal seabags, we also had a small cruisebox containing Navy advancement exams. With a fuel load of only three hours and more than 200 miles distance to the scene of action, we would require refueling before going “feet dry.”

Few aviators were privy to being summoned by Task Force 77 himself. When “god” speaks, you don’t ask questions. Emergency flight quar¬ters were immediately called. I was still in my flight gear and was the first person to arrive at the helo in total darkness, before the night deck edge lighting had been activated. I used my flashlight to remove the engine covers and pilot tube cover, and then made a final preflight check and strapped into the co-pilot seat. Bill was an equally experienced aircraft commander and I felt confident in his abilities to fly. By the time

our crew arrived, the checklist and other pre¬flight items had been completed and we were ready for launch.

Takeoff from a rolling deck only 12-15 feet above the waterline in a fully loaded HH-3A is a bit of a misnomer. It more closely resembles a wallowing animal, lumbering to remain on its feet. As we slipped over the deck edge at 22:20, all eyes focused on the radar altimeter as it held steady at 10 feet, until we gained enough air speed and entered translational lift. The radar altimeter finally showed a positive rate of climb and we began breathing a bit more freely.

Our initial steer was nearly due south for approximately 200 miles. After safely established and en route, I reviewed the scenario with our crew: an A-7 Corsair II was downed over North Vietnam approximately two hours ago, the pilot had ejected and there were still no voice commu-nications. Flying at only 500 feet with TACAN off to avoid electronic detection, we soon lost voice comms with England and would be on a DR steer for the next 40 or 50 minutes until voice comms were reestablished with Midway.

That time was used to brief the crew for various rescue scenarios, study our maps and prepare ourselves mentally. Combat SAR exercises at NAS Fallon, Nevada, flashed through my mind. This is exactly what we trained and practiced for; only this “CSAR-EX” would be for real. Mistakes at Fallon were handled with debriefs. A mistake tonight could be costly.

When we established comms with Midway, we learned that voice comms had been established with the downed pilot and other SAR forces were being positioned for a rescue attempt.

We were quickly passed known information, which was sketchy at best. The urgency of the situation deemed it inappropriate to request all of the information still lacking on my kneeboard card that had been paramount before progress¬ing with CSAR-EXs at Fallon. We had a pilot on the ground 21 miles inland and were marginal on fuel. We quickly concluded that if everyone was ready now, we would have enough fuel to reach the downed pilot’s position, conduct a 10-minute search, and still make it to a ship that was being dispatched toward the North Vietnam coastline.

Task Force 77 gave authorization and as we formed up to proceed feet dry, the downed pilot came up on voice and reported heavy enemy activity in his immediate vicinity, making a pick¬up impossible. At that point we requested vec¬tors to the nearest ship for fuel, and Big Mother 71 from USS Saratoga arrived on station and was

designated Primary SAR.

We switched frequency and departed to refuel. At the time we did not realize that pilot¬ing Big Mother 71 was our skipper, Commander Dave McCracken, a seasoned CSAR pilot. Our duties now turned to taking on fuel. We were vectored to USS Hepburn (DE-1055). Without a deck large enough to land H-3s, we would be required to do a night helicopter in-flight refuel¬ing, a process requiring hovering over the deck to pick up the fuel hose, then gently moving to the side and flying alongside as close to the water as possible to allow a quicker transfer of fuel from ship to helo. A tricky maneuver during daylight, this process was complicated by total darkness, a shorter-than-standard fuel hose and a low pressure fuel pump. Although these dif¬ficulties caused several “breakaways; we finally began taking on a positive rate of fuel flow. While monitoring the strike frequency, I learned that our skipper had to return to Saratoga because of a low fuel state and that the downed pilot had requested pickup. We were, again, the only helo available, and it would still take 10 minutes for another 500 pounds of gas—enough for a 30-minute cushion. I knew that time was of the essence. We already had enough fuel for a 15-minute search. I decided that would have to do. We cut fueling and proceeded to join up with our A-7 escorts. As two A-7s wagon-wheeled overhead, we penetrated “feet dry” just north of Vinh at approximately 0200.

After calling off the initial rescue effort due to heavy concentration of enemy troops, the downed pilot, VA- 105 Lieutenant Jim Lloyd, began pro¬ceeding to a “clear” area. While attempting to relo¬cate, he heard footsteps from behind and played dead as instructed in SERE school. Someone then prodded him in the back with a rifle barrel. Upon hearing footsteps leaving the area, he slowly turned as if in pain to “make a play” for the gun. To his astonishment, he saw two figures departing the area and no one else around. He quickly with¬drew and, after relocating, called again for a pickup. Until that point, the total blackness of the night had been his protection. On several occasions, enemy troops came within five or six feet of his location and had not spotted him. Daylight was only a few hours away and evasion would no longer be possible.

As we had no ECM equipment and were vul¬nerable to surface-to-air missiles, we ingressed as close to the terrain as possible, which was exceedingly hazardous because of poor visibil¬ity and obscuration of terrain by a broken cloud layer and lack of a horizon. Our first glimpse of land was an obscured outline of a 3,500-foot karst. At the moment I caught sight of the karst, words from Psalm 121 flashed through my thoughts; “I will look unto the hills from whence cometh my help. My help cometh from the Lord which made the heavens and the earth:’

At the scene of action, On-Scene-Commander (OSC) Commander Jim Earnest with Bombar-dier/Navigator Lieutenant Commander Grady Jackson, flying in A-6 Intruder 504, had already made several trolling passes in the area draw¬ing enemy fire while simultaneously attempting to locate Lloyd as a sight turnover had not been possible. Unable to raise Lloyd on guard, 504

turned on its lights and began flying low level in the area. Within minutes, Lloyd spotted 504 and gave him vectors to “on top” After marking his position, 504 then reestablished an orbit south of Lloyd’s position so as to not give away the downed pilot’s location.

From approximately five miles out, we spot¬ted 504 and he reported, “Big Mother, he’s below me” We found the haystack—now we had to find the needle. We immediately commenced a lights-off, high-speed instrument descent to 100 feet AGL.

As we neared the scene of action, we spotted a pencil flare at our nine o’clock. Earnest imme-diately replied that it was not Lloyd’s flare and that his position was approximately one half mile north of the flare. We immediately turned north and commenced, slowing down near a position we estimated to be a half-mile north of the flare. As we approached the hover, Earnest yelled in a pitched voice, “Big Mother get out of there! It’s a trap, he’s still about a mile north!”

All hell broke loose. As we applied full power to depart the area, we saw small arms fire from every direction. As we jinked left, the Radar Altimeter Warning System (RAWS) alerted us that we had descended below 30 feet AGL. As we jinked right the RAWS sounded again. I imme-diately turned on the controllable spotlight, and not a second too early. Illuminated directly in front of us was a tree line and the shadow of several small hooches. As we pulled collec¬tive to clear the treeline, I could see outlines of troops pointing weapons our way. I instinctively grabbed the controls and banked hard right as the sky lit up with small arms fire. I leveled the wings, and, after clearing the treeline, descended back down to approximately 30 feet. During this evolution, Airman Szymanski was returning fire from the forward M-60 machine gun mounted on the port side, silencing the enemy fire.

We could now hear Lieutenant Lloyd (call sign Canyon 407) shouting: “I’m at your six, I’m at your six!”

I passed aircraft control to Bill and we circled back. Again from Canyon 407 we heard: “I’m at your six, I’m at your six!”

Bill increased his rate of turn, aided by the spotlight. I called Canyon 407 to show his light. No response. Again I called, “Show your light, dammit, show your light!”

Lloyd finally responded and reported, “Strobe. Don’t fire”

Within seconds, several strobes and pencil flares were accompanied by heavy small-arms fire, which produced brilliant white flashes, creating certain amount of confusion. Airman Szymanski tapped me on the shoulder and while pointing to our left reported; “There is the first strobe that went off.”

As we banked left Lloyd called our vector to final, saying “Come left 10 degrees followed quickly by—your other left:’ As we rolled on final we visually sighted Lloyd running toward the

helo waving his arms. As we began transition-ing to a possible hover, first crewman Ankney exposed himself to enemy fire while lowering the jungle penetrator. At the last moment, determin¬ing the terrain suitable for landing, we elected to land to minimize our vulnerability to already heavy enemy fire. While Bill held Big Mother 60 a few inches off the ground, first crewman Ankney reached out and grabbed Lloyd by the shoulders and hauled him aboard. For an instant, Lloyd thought that he had been captured by the enemy. The time was 0223.

Commander Earnest, overhead in his A-6 Intruder, was the first to see the AAA site open fire on us from point blank range as we were transitioning to a hover. During the debriefing the next day, Commander Earnest remarked, “I thought you guys were goners”

With only Rockeyes on board, Earnest said the site was too close to do anything but watch

in disbelief. As Lieutenant Lloyd was hauled on board by Ankney, we could see the tracer rounds from the AAA site passing overhead. As later deduced, the enemy was saving the AAA site for the helo that the enemy hoped would come. Also, knowing that helos generally hover for rescues, they set the barrel for approximately 40 feet, a near-perfect altitude for hovering targets. As we opted to land vice hover, the gun could not be manually lowered in time for the kill before we deftly used ground effect to escape the increas¬ingly closer trajectories of the mobile AAA site. After we departed the area, Earnest expended his remaining Rockeye, silencing the AAA site.

With Lieutenant Lloyd safely on board, we began a max power egress, utilizing ground effect until approximately 40 knots. After receiving a vector of 080, we began a high-speed jinking run for the beach. The aging rotor blades of the H-3 had reduced the redline airspeed from 144 knots to 120 knots. If redline used to be 144 knots, I thought, surely this was a time it could be done again. Bill and I both remember seeing 156 knots before we could no longer read the instruments due to vibrations.

At nearly 10 miles from the scene of action, we were approaching the karst and about to relax when two fire trails passed on either side of the helo. We initiated an immediate autorotation. After clearing the karst, we continued the auto-rotation toward the barely visible beach.

Nearing the beach, I once again took control of the helo, giving Bill a well-deserved breather. As we crossed the coastline, I reported “feet wet” with the downed pilot safely on board.

We were given vectors to USS Cleveland (LPD-7), which had been dispatched to recover both our skipper and us. En route to Cleve¬land, both fuel-level warning lights illuminated. Again, I passed control to Bill for the approach and landing aboard Cleveland. He made a steep approach just in case of a power loss or flameout, neither of which occurred. A quick gear check by the deck crew ascertained both main mounts and tail wheel were intact. Bill ended the 4.7 hour flight with a landing that go-fasters might call an OK-3 wire. It was 03:00.

Between our morning launch from Midway to our final landing aboard Cleveland, we had logged 11.2 hours of flight time. The last 4.7 hours were flown in total darkness and almost entirely on instruments. A thorough preflight inspection the next morning revealed more than a dozen hits by small arms fire. One bullet had creased the tail rotor driveshaft, and a non-tracer round had punctured one of the self-sealing fuel cells.

Why didn’t Lloyd come up on voice for nearly three hours? After ejecting, Lloyd said that he had only one half-swing in his parachute before hitting the ground next to the flaming wreckage of his Corsair II. In his hurry to clear the area, he quickly rid himself of most gear, keeping only his PRC-90 and compass. After clearing the area and finding shelter in a bush, he reached for his PRC-90 and realized it was gone. He then spent the next two or three hours backtracking on his hands and knees, finally locating the radio, sub¬merged in a rice patty.

Lloyd’s reason for not immediately using his strobe was because it was fastened to his torso-harness. He said later that he wished he could have turned on his strobe and then thrown it away from him. Being fastened to his G-suit, this could not be done. On the other hand, he read¬ily admitted that had it not been sewn onto the harness, he may have lost it during the ejection or his evasion.

Despite our sporadic encounters of intense enemy fire, no one sustained any injuries and no mishaps with external obstacles occurred. Lieu¬tenant Bill Young’s brilliant airmanship from takeoff to landing cannot be overstated. Having two fully qualified pilots in demanding, night instrument combat conditions is a high confi¬dence factor. This rescue was a team effort of not only our crew, but all air and ship assets involved that evening. In the words of the rescued pilot, Lieutenant Jim Lloyd, “It’s fantastic what so many people will do to save one life”.

Zinser-Young-Lloyd-Ankeny-Szymanski

1) Numbering as per HC-7 Rescue Log (accumulative rescue number)

2) HC-7 Rescue Log

3) HC-7 Det 110 Rescue report – First page (no crew statements)

4) Map – Google Map

5) “Vietnam – Air Losses” By: Chris Hobson (with permission)

6) Loss aircraft location data provided by: W. Howard Plunkett (LtCol USAF, retired)

10) HC-7 History collection; Ron Milam – Historian

11) Unclassified Accident Report – B-1-40

NOTE: No deck log information – USS England, USS Saratoga, USS Midway.

Other references;

A. 1973-1975 HC-7 Command Report

B. HC-7 Helo Squadron Recues Downed Aviator Inside North Vietnam

C. USS Saratoga Association – web site

D. “To Those Who Returned for Me” by James R. Lloyd – THE HOOK – Winter 1997

E. “Aviator Rescue HC-7 Squadron Saves Lives” – ALL HANDS – Nov. 1972

F. “Search and Rescue” – Naval Aviation Library – Pistons to Jets

G. “Naval Aviation News” – October 1972 –

H. “Naval Aviation News” – November 1972 – “Inside Story”

I. “Navy Flier Credited for Behind the Lines Rescue”–Evening Tribune–San Diego– Aug-15-72

J. “Leave No Man Behind” by: George Galdorisi and Tom Phillips

(Compiled / written by: Ron Milam, HC-7 Historian – HC-7, 2-1969 to 7-1970, Det 108 & 113)